Most product teams build features that nobody asked for. They spend months refining something they believe customers want, only to watch it collect dust after launch. The root of this problem sits in a simple misunderstanding: teams focus on what they can build rather than why customers would care.

Clayton Christensen, a professor at Harvard Business School, spent years studying why products fail. His conclusion reshaped how companies approach development. Customers do not buy products. They hire them to accomplish something specific in their lives. A person does not want a drill. They want a hole in the wall. They do not want the hole either. They want the picture hung, the room looking finished, the satisfaction of completing a small project on a Sunday afternoon.

This thinking forms the foundation of the Jobs-to-be-Done framework. It strips away assumptions about demographics, user personas, and feature comparisons. Instead, it asks a direct question: what is this person trying to accomplish, and what stands in their way?

The framework has proven itself in practice. Outcome-Driven Innovation, which applies JTBD principles to product development, achieves an 86% success rate in launching new products. Compare that to the industry average, where most new products fail to gain traction. The difference comes down to starting with the right question.

Here, you will learn how to identify jobs, map customer needs, understand the forces that drive behavior change, and apply templates that make the framework usable within your team. By the end, you will have a working template you can adapt for your own product development process.

TL;DR

- JTBD focuses on what customers are trying to accomplish rather than what features they request

- Outcome-Driven Innovation using JTBD achieves an 86% success rate compared to typical product failure rates

- Jobs break into three types: functional, emotional, and social

- The Universal Job Map covers eight phases: define, locate, prepare, confirm, execute, monitor, modify, conclude

- Four forces determine switching behavior: push, pull, anxiety, and inertia

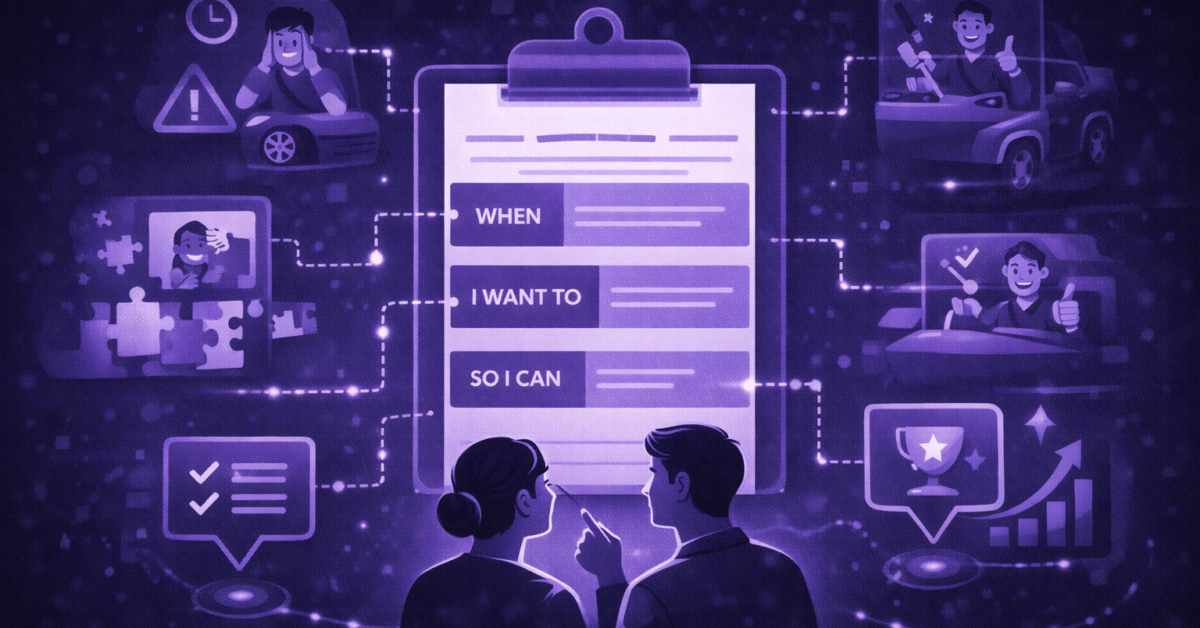

- Job statements follow the structure: When… I want to… So that I…

- Microsoft increased Software Assurance revenue by 100% after aligning their program with underlying customer jobs rather than product features

- Traditional JTBD research takes 3 to 4 weeks, creating friction with sprint timelines

- Hybrid approaches using predictive validation using Evelance followed by targeted interviews compress research cycles without sacrificing depth

- The provided template covers customer definition, job mapping, force analysis, success metrics, and interview guides

What the JTBD Framework Actually Measures

The JTBD framework measures progress. Not satisfaction. Not preferences. Progress toward a specific outcome that matters to the customer.

When someone hires a product, they are trying to move from their current state to a better one. A parent buying a meal kit service is not interested in the ingredients themselves. They are trying to solve the problem of feeding their family a decent meal without spending two hours planning and shopping. The meal kit is the vehicle. The job is the destination.

This distinction matters because it changes what you ask during research. Traditional surveys might ask how much someone likes a feature. JTBD research asks what the customer was trying to accomplish when they chose to use that feature. One approach collects opinions. The other uncovers intent.

Jobs break down into three types. Functional jobs describe the practical task at hand. Cutting a piece of wood, filing taxes, booking a flight. Emotional jobs describe how someone wants to feel during or after the task. Feeling secure, staying calm under pressure, avoiding embarrassment. Social jobs describe how someone wants to be perceived. Gaining status, appearing competent, fitting in with a group.

A single purchase often addresses all three. Someone buying a luxury watch is solving a functional job (telling time), an emotional job (feeling successful), and a social job (signaling status to others). Product teams that only address the functional layer miss two thirds of the story.

The Universal Job Map

Tony Ulwick, who developed Outcome-Driven Innovation, created the Universal Job Map to structure how teams think about customer needs. The map breaks every job into eight sequential steps. These steps remain consistent across industries, products, and customer types.

Define

The customer determines what they need to accomplish. They set goals, plan their approach, and decide what resources they will need. A homeowner planning a renovation defines the scope of work, sets a budget, and outlines what they want the finished space to look like.

Locate

The customer gathers the inputs required to complete the job. They find materials, information, or services. The homeowner researching contractors, comparing prices, and reading reviews is in the locate phase.

Prepare

The customer sets up their environment or organizes what they have gathered. The homeowner clears furniture, prepares surfaces, and makes the space ready for work.

Confirm

The customer validates that they are ready to proceed. They check that everything is in place and that conditions are right. The homeowner confirms the contractor’s schedule, verifies permits are approved, and ensures materials have arrived.

Execute

The actual task takes place. This is where most product teams focus their attention, but it represents only one of eight opportunities to add value.

Monitor

The customer tracks progress to ensure the job stays on course. The homeowner checks in on the renovation, reviews timelines, and watches for problems.

Modify

The customer makes adjustments when things do not go according to plan. Budget overruns, unexpected issues, or changes in preference all require modification.

Conclude

The customer completes the job and moves on. They finish the project, evaluate the outcome, and handle any remaining tasks like cleanup or documentation.

A job map does not show what the customer does. It describes what the customer is trying to get done. This distinction separates a solution-focused view from a needs-focused view. When you map the job rather than the user journey, you find opportunities that competitors miss.

The Four Forces Model

Customers do not switch products on a whim. Four forces interact to determine when someone abandons their current solution and adopts something new. Two forces push toward change. Two forces hold customers back.

Push: Problems With the Current Situation

This force describes the frustrations, limitations, and pain points in how the customer currently solves the problem. A team using spreadsheets to track projects might face version control issues, lost updates, or difficulty collaborating across time zones. These problems create pressure to find something better.

Pull: Attraction to a New Solution

This force describes what makes the new option appealing. The team sees a project management tool that promises automatic syncing, real-time updates, and clear visibility across the team. The appeal of these features pulls them toward switching.

Anxiety: Concerns About the New Solution

This force describes the fears and uncertainties around adopting something different. Will the new tool actually work as advertised? Will the team adopt it or ignore it? Will data migrate smoothly? These anxieties slow down the decision to switch.

Inertia: Resistance to Change

This force describes everything that makes staying with the current solution easier than switching. Familiarity, sunk costs, existing workflows, and simple habit all contribute to inertia. Even when the current solution causes problems, inertia can keep customers stuck.

For a customer to switch, push and pull must outweigh anxiety and inertia. Product teams can use this model to diagnose why customers are not adopting. If push and pull are strong but adoption remains low, the problem likely sits with anxiety or inertia. Addressing those specific forces can unlock growth.

Microsoft provides a useful example. Their team discovered that customers buying Software Assurance were not motivated by getting updates. The underlying jobs were optimizing IT budgets, managing risk, and reducing disruptions. When Microsoft redesigned their program around these jobs rather than the product features, they saw a 100% year-over-year revenue increase. The features did not change. The positioning did.

Writing a JTBD Statement

The standard format for a job statement follows a specific structure: When… I want to… So that I…

This structure covers three components. The context describes the situation that triggers the job. The task describes what the customer is trying to accomplish. The outcome describes why accomplishing that task matters.

- A poorly written job statement might read: “Customers want better reporting.” This statement lacks context, specificity, and outcome. It describes a feature request rather than a job.

- A properly written job statement might read: “When I need to update stakeholders on project status, I want to generate a summary without manual data entry so that I can spend my time on the work itself rather than reporting on it.”

This statement identifies when the job arises (update meetings), what the customer wants to accomplish (generate a summary automatically), and why it matters (reclaim time for actual work). It also points toward specific product opportunities. Automatic data aggregation. Configurable report templates. Scheduled distribution.

The “so that” portion often reveals the actual job. The surface request (a report) is the means. The outcome (reclaiming time) is the end. Products that address the outcome rather than the surface request often outperform competitors who focus on feature matching.

Gathering JTBD Research

Traditional JTBD research relies on customer interviews. You speak with people who recently made a purchase decision or switched solutions. You walk through the timeline of their decision. When did they first recognize a problem? What did they try before finding your product? What almost stopped them from switching? What finally pushed them over the line?

This research produces rich qualitative data. You hear the language customers use to describe their problems. You uncover jobs that surveys would never reveal. You find the anxieties and inertia that block adoption.

The problem is time. Product teams operate in 2-week sprints. Traditional research projects take 3 to 4 weeks from recruitment through analysis. By the time insights arrive, the team has already moved forward without them. Or the team waits, slowing development and frustrating stakeholders.

This timing mismatch explains why 95% of product teams do not agree on what a customer need even is. The research that would create alignment takes too long to influence decisions.

How Evelance Supports JTBD Research

Evelance addresses the timing problem without sacrificing depth. The platform uses predictive personas to run initial validation before live research begins. Teams can test assumptions about customer jobs in under 10 minutes rather than waiting weeks for recruitment and scheduling to complete.

One team reported that collecting feedback from 23 people took 3 weeks when accounting for recruiting, scheduling, follow-ups, and compiling responses. Predictive testing delivered comparable insights in under 10 minutes. The team then used live interviews to explore the specific issues that surfaced, focusing their limited research time on questions that actually needed human depth.

This hybrid approach fits sprint timelines. Teams run quick validation at the start of a cycle, proceed with development based on initial findings, and schedule targeted interviews to address remaining uncertainties. Research becomes a continuous input rather than a gate that blocks progress.

The model works because it augments existing research workflows rather than replacing them. JTBD research still benefits from hearing customers describe their problems in their own words. Evelance compresses the early phases of validation so that human conversations can focus on what matters most.

Common Mistakes When Applying JTBD

Teams new to the framework often make predictable errors. Avoiding these saves time and improves the quality of research.

Confusing Jobs With Solutions

A job describes an outcome. A solution describes a means to that outcome. “Customers want a mobile app” is a solution. “Customers want to complete tasks while away from their desk” is a job. The distinction matters because jobs remain stable while solutions change. Someone who wanted to listen to music while running had the same job in 1985 and 2024. The solutions ranged from a Walkman to a smartphone.

Writing Jobs That Are Too Broad

“Customers want to be productive” applies to everyone and reveals nothing. Jobs need specificity to be useful. Who is the customer? When does the job arise? What specific outcome defines success? Narrower jobs lead to actionable insights.

Writing Jobs That Are Too Narrow

“Customers want to save files as PDFs” describes a feature rather than a job. The underlying job might be “share documents that look the same on any device.” PDF export is one solution. Understanding the job opens up alternatives.

Ignoring Emotional and Social Jobs

Functional jobs are easier to identify. Emotional and social jobs require deeper conversation. A customer might say they chose your product because of price, but the underlying motivation could be avoiding criticism from their manager for overspending. Surface reasons often mask emotional or social factors.

Stopping at the Job Statement

A well-written job statement is a starting point, not an endpoint. Teams need to identify the metrics that define success for that job, the obstacles that prevent success, and the current solutions that customers are hiring. A job statement without supporting research produces the same guesswork that the framework was designed to eliminate.

Comprehensive JTBD Template

This template provides a working structure for applying the framework within your team. Adapt it based on your product, customer type, and research capacity.

Part 1: Customer Definition

Who is the job performer?

Describe the person doing the job in specific terms. Avoid generic labels like “business user” or “consumer.” Include relevant context such as role, environment, or constraints.

Example: Marketing managers at mid-size companies who report to a CMO and manage a team of 3 to 8 people.

What is their current situation?

Describe how they solve the problem today. Include the tools, processes, and workarounds they use. Note pain points and limitations.

Example: They track campaign performance using spreadsheets exported from multiple platforms. Data is manually combined and updated weekly. Reports take 2 to 3 hours to compile.

Part 2: Job Statement

When [context/trigger]

I want to [task/action]

So that I [outcome/motivation]

Example: When I need to demonstrate marketing ROI to leadership, I want to combine data from all campaign sources automatically so that I can focus on analysis rather than data collection.

Part 3: Job Map

Complete each phase with specific outcomes the customer is trying to achieve.

| Phase | Customer Outcome |

| Define | What does the customer need to determine before starting? |

| Locate | What inputs does the customer need to gather? |

| Prepare | How does the customer set up for the job? |

| Confirm | What does the customer need to verify before executing? |

| Execute | What happens during the core activity? |

| Monitor | What does the customer track during execution? |

| Modify | What adjustments might the customer need to make? |

| Conclude | How does the customer finish and evaluate success? |

Part 4: Job Types

Functional job:

The practical task the customer is trying to complete.

Example: Aggregate data from 5+ marketing platforms into a single view.

Emotional job:

How the customer wants to feel during or after the job.

Example: Feel confident when presenting to leadership. Avoid anxiety about defending numbers.

Social job:

How the customer wants to be perceived by others.

Example: Appear data-driven and strategic to the executive team.

Part 5: Four Forces Analysis

Push (problems with current situation):

List specific frustrations, limitations, and pain points.

- Manual data entry introduces errors

- Reports are outdated by the time they are presented

- Time spent on compilation reduces time for analysis

Pull (attraction to new solution):

List features, benefits, or outcomes that attract the customer to switch.

- Automatic data syncing across platforms

- Real-time updates without manual intervention

- Professional visualizations that impress stakeholders

Anxiety (concerns about new solution):

List fears, uncertainties, and risks the customer associates with switching.

- Will data accuracy be maintained during migration?

- Will the team actually use it or revert to spreadsheets?

- What happens if the platform goes down before a presentation?

Inertia (resistance to change):

List factors that make staying with the current solution easier.

- Familiarity with existing spreadsheet process

- Time investment in current templates

- Resistance from team members who prefer existing tools

Part 6: Success Metrics

List the outcomes that define success for this job. Use the format: [Minimize/Maximize] + [Metric] + [Context]

Example:

– Minimize time required to compile cross-platform data

– Minimize errors in reported figures

– Maximize confidence in data accuracy

– Minimize questions about methodology from leadership

Part 7: Competitive Alternatives

List all solutions the customer currently hires to accomplish this job. Include products, services, manual processes, and doing nothing.

| Alternative | Strengths | Weaknesses |

| Spreadsheets | Familiar, flexible, free | Manual, error-prone, time-consuming |

| Platform-native reports | Automated, accurate | Siloed, cannot combine sources |

| Hiring an analyst | High quality output | Expensive, slow, dependency |

| Presenting less data | Simple | Appears less strategic |

Part 8: Interview Questions

Use these questions during customer interviews to uncover job details.

Discovery questions:

– Walk me through the last time you needed to [accomplish job]. What did you do?

– When did you first realize [current solution] was not working well enough?

– What did you try before you started using [current solution]?

Push questions:

– What frustrates you most about how you handle this today?

– What usually goes wrong?

– How much time does this take compared to how much it should take?

Pull questions:

– What would an ideal solution look like?

– If this problem were solved, what would you do with that time/money/energy?

Anxiety questions:

– What concerns would you have about trying something new?

– What would need to be true for you to feel confident in a different approach?

Inertia questions:

– What makes your current process hard to abandon?

– Who else would need to be involved in a decision to change?

Part 9: Opportunity Scoring

Rate each outcome from Part 6 using the formula: Importance + (Importance – Satisfaction) = Opportunity Score

Higher scores indicate greater opportunity. Focus product development on outcomes with high importance and low satisfaction.

| Outcome | Importance (1-10) | Satisfaction (1-10) | Opportunity Score |

| Minimize data compilation time | 9 | 3 | 15 |

| Minimize reporting errors | 8 | 4 | 12 |

| Maximize presentation confidence | 7 | 5 | 9 |

Putting the Framework Into Practice

The gap between understanding JTBD and applying it successfully comes down to consistency. Teams that run job-based research once and return to feature-focused development miss the point. The framework works when it becomes the default lens for evaluating opportunities, writing requirements, and measuring success.

- Start with a single product area. Use the template to document the primary job your customers are trying to accomplish. Interview 5 to 8 customers who recently made a decision to use or abandon your product. Map their responses to the four forces model. Identify where your product creates pull and where anxiety or inertia blocks adoption.

- The research will surface opportunities that feature requests never revealed. Customers describe their frustrations and desired outcomes in language that shapes better product decisions. When the entire team shares a common view of the job, debates about features become discussions about which approach best serves the underlying need.

- Apply the framework to roadmap planning. Score opportunities based on importance and current satisfaction. Prioritize development where the gaps are largest. Test new concepts against the job map to ensure they address real phases of the customer’s process rather than adding capability nobody asked for.

JTBD does not replace intuition or domain knowledge. It provides structure for conversations that often drift into opinion and assumption. When someone on the team asks “but what job does this help the customer accomplish,” the discussion stays grounded in what matters.

Jan 08,2026

Jan 08,2026